Black Hair, Media & America:

A twisted history

- NHP

- Going Natural 101

- Black Hair Media

DISSERTATION: Black Hair, Media & America: A twisted history.

“Don’t touch my hair!”

This strong sentiment has been widely-adopted as the fervent battle cry of the 21st-century Natural Hair Movement.

And it makes sense.

Because in actuality, "Don't touch my hair" has long been the heartfelt inner-feelings of the entire African-American community, men, women, and children since the days of early American enslavement.

Fact is, one of the first offenses against enslaved Africans was the forceful, unwanted cutting off of their hair.

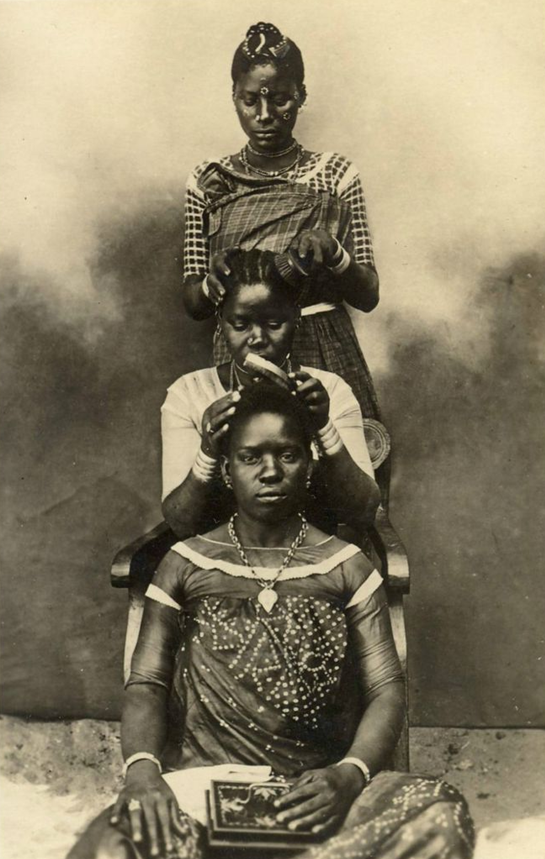

The Status of African Hairdressers

- Black Hair Media

In ancient times hairdressers held relatively high status in traditional African cultures as time for hair-grooming was seen as an opportunity for community-building socialization.

In Senegal, Ghana and most African communities, hairdressers work only with members of their own gender.

Hairdressing, often done daily, involves cleansing, then combing, oiling, and styling into braids, twists, wraps, curls, or other variations, often with decorative accessories.

The Rich History of African Hair - Black Hair Media

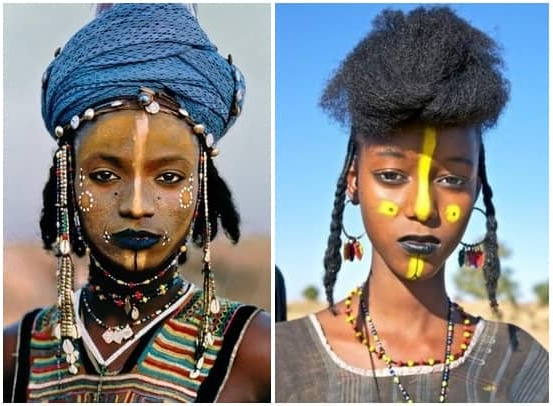

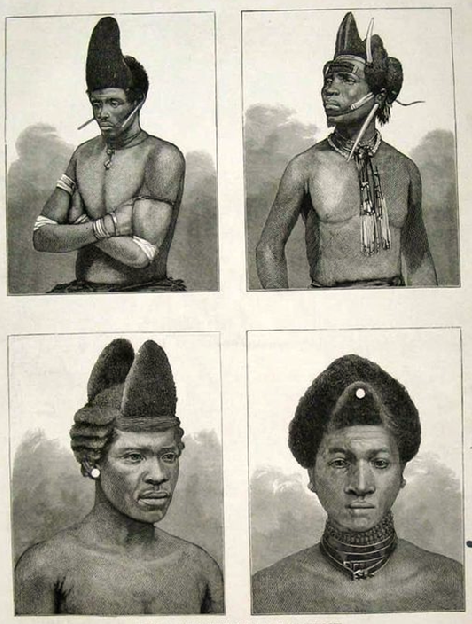

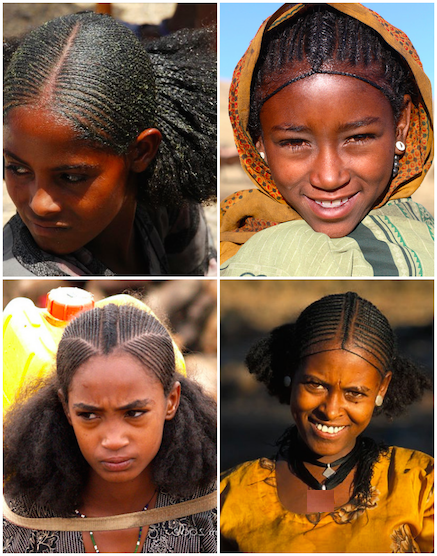

The amazingly unique and diverse hair textures of African women and men varies from Eastern Africa all the way to Western Africa.

Some scientists have attributed the conditions of African geography to the type of hair texture a particular group of Africans may have.

The social significance of an African’s hairstyle speaks for itself.

You can tell much about an African man or woman by observing their hairstyle of choice.

African hairstyles have revealed a person’s marital status, birthplace, clan membership, age, occupation, and socioeconomic status.

An example is the Kuramo men of Nigeria, who could be spotted from afar by their partially shaved heads, with just one tuft of hair on top.

Among the Masai, warrior males are recognized by their long braids dyed with red clay, while the women and children traditionally keep their heads shaved.

The more elaborate hairstyles were worn by community leaders, and the ruler, who was the only one permitted to wear a headdress. Beautiful crowns were fashioned out of leather, gold, beads, and fancy braids.

Single young women may wear styles that show they are open to marriage, whereas married women’s hairstyles show that they are already taken.

Before marriage, Igbo girls in present-day Nigeria use clay, ground coal and palm oil to shape their hair into a horn-shape that bends toward their brows. While married women have plainer, covered styles, girls in Senegal wear braids and whimsical styles.

Photographer: Joey Rosado, Island Boi Photography

Model: Khoudia Diop, @melaniin.goddess

If a young woman of Senegal’s Wolof people was not of marrying age, she would have to shave her head a certain way, while men of this same group would braid their hair a particular way to show preparation for war and therefore the preparation for death.

In Kenya, young Turkana men spend hours getting their hair styled elaborately to show they had completed the initiation rites for adulthood.

BLACK HAIR MEDIA:

Attraction & Social Connotations of Hair in Africa

African hair also has clear social and attraction connotations. Most societies view long, thick, neatly-styled hair on a young woman as a sign of fertility, health, and respectability – qualities that make them desirable as mates.

In traditional African cultures, both men and women groomed their hair, and unkempt hair was a sign of mourning, illness or antisocial behavior.

In some ancient societies, African men wore their hair in a distinctive style when they were about to go to war.

This gave an unverbal signal to their families to prepare for a possible death.

[ Photo Credit @ www.afrographics.com ]

BLACK HAIR MEDIA:

Braiding Throughout African History

The discovery of ancient stone carvings and paintings depicting North African women and men with cornrow braids dating back thousands of years show the rich history between Africans and hair braiding..

In their earliest known forms on the African continent, braided styles had a duality of purpose:

Not only did they uphold societal customs, but they were also highly fashionable. “African women have a rich history in terms of the ways they adorn their hair,” says Zinga A. Fraser, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Brooklyn College.

[See NHP's list of Black-Owned Hair Product Businesses]

The dichotomy between tradition and artistry existed in perfect harmony until the start of the transatlantic slave trade in the fifteenth century.

The Himba woman pictured below is married as she is wearing ornaments on top of her braided hair. These ornaments, which young unmarried girls do not wear, identify her as being a wife.

Note also the ornaments and conch shell that hangs below her necklace, which is only worn by married women and is a seen as a symbol of fertility.

Did You Know?

Bronze head, kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, early 16th century. - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bronze head, kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, early 16th century. - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.Benin Bronzes are a group of more than a thousand metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin in what is now modern-day Nigeria.

Collectively, the objects form the best known examples of Benin art, created from the thirteenth century onwards, by the Edo people, which also included other sculptures in brass or bronze, including some famous portrait heads and smaller pieces.

In 1897 most of the plaques and other objects were looted by British forces during a punitive expedition to the area as imperial control was being consolidated in Southern Nigeria.

Two hundred of the pieces were taken to the British Museum, London, while the rest were purchased by other European museums.

Today, a large number are held by the British Museum.

Other notable collections are in Germany and the USA.

The 1st Cut Was The Deepest | Black Hair Media

- The Big Chopping of African Roots

The impact of slavery on African's can not be overstated.

In addition to the physical and psychological trauma it caused, a huge part of the very essence of these enslaved human being was erased.

During the 1400s and 1500s, before European slave ships arrived in Africa, the hairstyle was very important to black women. Many would spend hours, or even days, on their hair, using special combs and oils to form locks, plaits, and twists.

[The adornment of both the head and hair was an essential part of the dress, especially in West Africa, where most blacks in America have their origins.

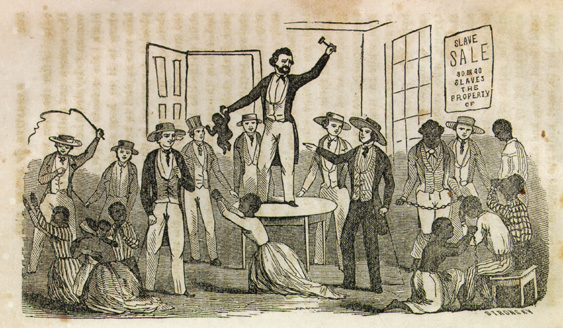

It was the year 1444 that the first documented slave trade happened.

Europeans began kidnapping Africans and trading them on the west coast of Africa.

The slaves wore their elaborate hairstyles to Europe. At first look, Westerners admired the hairstyles, but they soon began to shave the enslaved human beings against their will.

Within years...

Even before captured Africans boarded the slave ships, the slave traffickers shaved the heads of the people in a brutal attempt to strip them of their humanity and culture.

They sought to take away the women’s lifeline to their homeland.

This was considered an unspeakable crime to many tribes. And...

Soon African hairstyles would disappear as the brutally enslaved human beings became more hopelessly lost, both physically and psychologically, under a system of unified oppression.

[ See article about kinky curly hair oils and hair health ]

Our First Tastes of Freedom

And its effect on the new perception of Black beauty | Black Hair Media

In the 1800s, ships stopped bringing slaves to the U.S. for sale. Slaves became more valuable as property.

In the 1800s, ships stopped bringing slaves to the U.S. for sale. Slaves became more valuable as property.In the 1800s, ships stopped bringing slaves to the U.S., in turn, the market value of slaves increased.

With this being the case.

Enslaved men, women and children were no longer forced to slave on Sundays, since literally working slaves to death at a whim(or for fun) would now start to cost more money than U.S. enslavers would have liked to pay.

This solely fiscally-motivated reprieve gave enslaved African women and girls one day of the week to have a few hours of "peace", and feel somewhat pretty again.

Enslavers would often twist the Bible's true message into something sinister and self-serving on Sundays and force their enslaved human men, women and children to attend church in order to indoctrinate a twisted message that the Bible doesn't really teach and has been maligned over ever since.

During the week, enlaved African women and girls would continue to cover their heads with a wrap but would remove it on Sunday for church.

However, they still weren't afforded the freedom or needed supplies to again display their beloved African hairstyles.

The fact that the combs they had previously used, and African hair products like palm oil was not available in America, they instead had to wash and condition their hair using butter, kerosene and bacon grease and brushed it with the carding combs used for the sheep. ( See our DIY natural hair products HERE )

The Beginning of the "Good Hair" Logical Fallacy

- Black Hair Media

During the insufferable years leading up to the abolition of slavery, many Black women wanted to straighten their hair, as straight hair had come to be considered, among some, as "good hair" because of the influence by the dominant society.

At no fault to whom the dominant society named "mulattoes", these mixed-raced humans were put in a precarious situation by a systematically oppressive society.

African women would often use dangerous chemicals, such as lye mixed with potato. The notion of “good hair” was further cemented because of house slaves or free Blacks, who often were born with straighter or straight hair because they were at least partially white.

However, the very limited sense of freedom these people enjoyed was not often due to their straight hair texture but rather due to the help they received from their white relatives.

Black Hair Media Films & Documentaries

This "Black Hair, Media & America" film and documentary gallery is dedicated to shining a light on the cause and effects of bias against Africans, as well as their hair and beauty in the United States of America.

This systematic and constant oppression against enslaved Africans and their descendants has left a deep, painful and long-lasting bruise on the very psyche of the subjects of said oppression.

History Of African Hairstyles Used As Maps To Escape Slavery

Black Women’s Hair Throughout History

- BLACK HAIR MEDIA

The Psychology of Black Hair | Johanna Lukate

- TEDx Cambridge University | BLACK HAIR MEDIA

No. You Cannot Touch My Hair! | Mena Fombo

- TEDx Cambridge University | BLACK HAIR MEDIA

This is Good Hair, Too:

A Black Hair Media Documentary

Our Hair-itage - A Natural Hair Documentary

(PBS Version) - Black Hair Media

The Evolution of Natural Hair On Screen

Black Hair Media

The History of African Women & Their Hair - Black Hair Media

What They Won't Tell You About Your Natural Hair

Part 1 & part 2

Braids and Appropriation in America

- Black Hair Media Documentary

Black Hair Media: The History of Braids & Bans on Black Hair

The History of Black Hair - Black Hair Media

REFERENCES

Ashe, B.D. (1995) “Why don’t he like my hair?” Constructing African-American Standards of Beauty in Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon and Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes were Watching God. African American Review, 29, 579- 592. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3042151

Bey, J. (2011) Going natural requires lots of help. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/09/fashion/hair-care-for-african-americans.html?_r=0

Bodenhorn, H. and Ruebeck, C. (2007) Colourism and African American wealth: Evidence from the nineteenth century south. Journal of Population economics, 20, 599-620. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0111-x

Bonvillain, J.F. and Honora, D. (2004) Racial identity attitudes, self-esteem, and academic achievement among African American adolescents. Reports/Research.

Byrd, A. and Tharps, L. (2001) Hair story: Untangling the roots of black hair in America. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Byrd, C. and Chavous, T. (2009) Racial identity and academic achievement in the neighborhood context: A multilevel analysis. Youth Adolescence, 38, 544-559. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9381-9

Carson, L. (2009) “I am because we are”: Collectivism as a foundational characteristic of African-American college student identity and academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 12, 327-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11218-009-9090-6

Chapman, Y. (2007) “I am not my hair! Or am I?”: Black women’s transformative experience in their self perceptions of abroad and at home. Master’s thesis. http://digitalarchive.gsu.edu/anthro_theses/23

Chavous, T.M., Rivas-Drake, D., Smalls, C., Griffin, T. and Cogburn, C. (2008) Gender matters too: The influences of school discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement among African American adolescent boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 44, 637-654. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637

Dash, P. (2006) Black hair culture, politics and change. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 10, 27-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603110500173183

Degruy, J. (2006) Post-traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing. Uptown Press, Baltimore.

Desmond-Harris, J. (2009) Why Michelle’s hair matters. Time, 174, 55-57.

Eccles, J., Wong, C. and Peck, S. (2006) Ethnicity as a social context for the development of African American adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 407-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.001

Etemesi, B. (2007) Impact of hair relaxers in women in Nakuru, Kenya International. Journal of Dermatology, 46, 23- 25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03458.x

Gates, R. (1957) 98. Forms of hair in South African races. Man, 57, 81-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2794242

Haley, A. (1973) The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley. A One World Book, New York.

Hall, R. (1992) Bias among African Americans regarding skin color: Implications for social work practice. Research on Social Work Practice, 2, 479-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104973159200200404

Healy, M. (2011) ‘Natural’ hair making waves among Black women. USA Today. https://www.pressreader.com/usa/usa-today-us-edition/20111222/290842301964287

Hughes, M. and Hertel, B.R. (1990) The significance of color remains: A study of life chances, mate selection, and ethnic consciousness among Black Americans. Social Forces, 68, 1105-1120

Jere-Malanda, R. (2008) Black women’s politically correct hair. New African Woman, 14-18.

Johnson, A., Godsil, R., MacFarlane, J., Tropp, L. (2017) The “Good Hair” study: Explicit and implicit attitudes toward Black women's hair. https://perception.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/TheGood-HairStudyFindingsReport.pdf

Johnson, T. (2014) Hair It Is: Examining the Experiences of Black Women with Natural Hair https://file.scirp.org/pdf/JSS_2014010814473478.pdf

Morrow, W. (1973) 400 years without a comb: The untold story. Black Publishers, San Diego.

Nasim, A., Roberts, A., Harrell, J. and Young, H. (2005) Non-cognitive predictors of academic achievement for African Americans across cultural contexts. The Journal of Negro Education, 74, 344-358.

Robinson, J. and Biran M. (2006) Discovering self: Relationships between African identity and academic achievement. Journal of Black Studies, 37, 46-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0021934704273149

Rooks, N. (1996) Hair raising: Beauty, culture and African American women. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick.

Rosenberg, M. (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Tate, S. (2007) Black beauty: Shade, hair and anti-racist aesthetics. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30, 300-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870601143992

Thompson, C. (2009) Black women, beauty, and hair as a matter of being. Women’s Studies, 38, 831-856. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00497870903238463

Webb, T., Looby, J. and Fults-McMurtery, R. (2004) African American men’s perceptions of body figure attractiveness: An acculturation study. Journal of Black Studies, 34, 370-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0021934703254100

Wise, L., Palmer, J., Reich, D., Cozier, Y. and Rosenberg, L. (2012) Hair relaxer use and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 175, 432-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr351